Abstract

Narcissism is often seen as a unidimensional construct, however, more recently, a plethora of studies have pointed to its multidimensional nature. Despite this, the role of narcissism as a multifaceted construct in the quality of interpersonal relationships has rarely been tested. In addition, less is known about what mechanisms may underly this association. In this study, we investigated how grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated narcissism, are associated with relational capacity and whether identity integration and social concordance may underly these associations. The sample included 222 male participants with a mean age of 37.71 (SD = 13.25). Of these, 157 were participants from the community, and 65 were in outpatient treatment at four Dutch forensic centers. The Dutch Narcissism Scale was used to measure three forms of narcissism, while The Severity Indices of Personality Problems – Short Form was used to measure identity integration, social concordance, and relational capacity. The mediation model was tested in R and adjusted for age and criminal behavior. Despite significant bivariate correlations between three narcissistic types and relational capacity only isolated narcissism was directly and negatively associated with relational capacity in the mediation model. Likewise, both identity integration and social concordance were positively associated with relational capacity. Grandiose narcissism was positively, while vulnerable narcissism was negatively associated with relational capacity, but only through identity integration. Identity integration was also a significant mediator in the association between isolated narcissism and relational capacity along with social concordance. Finally, criminal behavior appeared to be the only significant covariate indicating that forensic outpatients (versus community participants) were more likely to have impaired relational capacity. The findings of this study could be useful in clinical practice to improve the treatment of narcissistic individuals and make them less harmful to others in social and intimate relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Toward a clarification of the concept of narcissism

Narcissism was initially conceptualized as a unitary construct referring to self-love, inflated self-images, self-serving bias, and demanding display of entitlement (Campbell et al., 2006; Kernberg, 1967; Twenge & Campbell, 2009). In the 1990s, however, this conceptualization of narcissism was broadened into two subdimensions, namely grandiose (or overt) and vulnerable (or covert; Wink, 1991). Although these two forms of narcissism share some common characteristics such as grandiose fantasies, a sense of entitlement, and the exploitation of others (Pincus et al., 2009), they can manifest in very different ways. Individuals with high narcissistic grandiosity are characterized by arrogance, grandiosity, egoism, and a lack of empathy. When threatened, they employ maladaptive strategies, such as the devaluation of others to keep their self-esteem high (Pincus et al., 2014). In contrast, individuals with high narcissistic vulnerability are more likely to be shy, embarrassed, and anxious; their self-esteem is fragile and accompanied by anger and irritability when threatened (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Pincus et al., 2009). In addition to grandiose and vulnerable dimensions, Ettema and Zondag (2002) suggested a possible third dimension of narcissism called isolation. This dimension relates to the separation between self and others and the feeling of not being known and understood by them. Individuals who feel isolated believe they are being criticized by people who have little respect for who they really are and are disappointed that others do not realize this. This isolation dimension usually concurs with vulnerable narcissism (Ettema & Zondag, 2002). Like vulnerable narcissism, isolation narcissism is considered dysfunctional (Ettema & Zondag, 2002), while grandiose narcissism is seen as a healthier subtype of narcissism compared to these two (Sedikides et al., 2004). Although many scholars have indeed considered the multifaceted nature of narcissism in their research (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Miller & Campbell, 2008; Wink, 1991), most of the studies conducted to date on the role of narcissism in the quality of interpersonal relationships have treated narcissism as a unitary construct (Barelds et al., 2017; Chin et al., 2017). Therefore, research is needed on the associations of different forms of narcissism with relational capacity. In addition, it remains unclear what mechanisms may underlie this association. In the present study, we attempt to fill these gaps in the literature.

Narcissistic traits and relational capacity

There is evidence that grandiose, vulnerable and isolated narcissism affect the individual’s relational capacity and the ability to relate to others. In the present study, relational capacity refers to the capacity to sincerely care for and connect with others, feel a sense of belongingness, and communicate personal experiences in (long-term) relationships (albeit not necessarily exclusive; Verheul et al., 2008). Specifically, higher levels of grandiose narcissism were linked to less avoidance within interpersonal relationships (Campbell et al., 2006; Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Rohmann et al., 2012), while higher levels of vulnerable narcissism were linked to more social withdrawal, feelings of insecurity and anxiety about possible rejection (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Rohmann et al., 2012; Smolewska & Dion, 2005). Grandiose narcissists have also been found to score higher on social-cognitive skills, such as perspective-taking, emotional intelligence, social reasoning, and empathy (Vonk et al., 2013). It is believed that they use these skills to manipulate others to reinforce their endless identity needs for superiority (Jonason & Webster, 2012). In addition, individuals high in narcissistic grandiosity are more likely to report low interpersonal distress and secure attachment styles associated with positive self-representation. When interacting with others, they tend to be dominant and assertive and generally see themselves positively, although others prefer to describe their actions negatively. Therefore, grandiose narcissists are considered to have difficulty understanding the impact of their behaviors on others (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Miller et al., 2007), and any conflict in the environment is attributed externally and not seen as a consequence of their behavior and unrealistic expectations.

Vulnerable narcissists maintain their self-esteem by avoiding criticism and judgment from others, which leads to more insecure behaviors (Vonk et al., 2013). Research has shown that they are less able to understand the feelings and thoughts of others (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001; Vonk et al., 2013). Thus, their heightened sensitivity to the judgment of others may stem partly from a tendency to misinterpret others’ feelings and thoughts, which can lead to severe self-focus and an inability to respond appropriately (Aradhye & Vonk, 2014). Interpersonal coldness and social avoidance of vulnerable narcissists mainly result from their difficulty in managing their vulnerability in interpersonal relationships. To ensure this, they are more likely to withdraw socially, either in an avoidant or a cold, distanced way (Cooper, 1981, 1998). Similarly, isolated narcissists are more likely to separate themselves from others because of their excessive need for self-preoccupation (Ettema & Zondag, 2002). In addition, they distance themselves from others because they believe they cannot recognize and understand their worth (Ettema & Zondag, 2002). Furthermore, compared to their grandiose counterparts, vulnerable narcissists reported greater interpersonal distress and were more likely to experience conflict around their entitled expectations (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003). This can result in a fast response to frustration and a risk of violence. Indeed, narcissistic vulnerability (but not grandiosity) was found to be an important driver for aggressive and or criminal behavior, fueled by suspiciousness, dejection and angry rumination (Krizan & Johar, 2015; Pincus et al., 2009). Although previous studies that treated narcissism as a one-dimensional construct generally reported that narcissistic individuals are overrepresented among criminals (Hepper et al., 2014; Larson et al., 2015), a recent study found that violent offenders were characterized by higher levels of vulnerable narcissism, while higher levels of grandiose narcissism were more characteristic of the community controls (Bogaerts et al., 2021). The isolation dimension has been rarely investigated, but due to its similarity to the vulnerable dimension, it has been suggested that isolated narcissists may display more maladaptive behaviors in various areas of life, including interpersonal functioning compared to their grandiose counterparts (Ettema & Zondag, 2002).

Despite a scarcity of studies in this area, the findings have shown that grandiose narcissists have a better capacity to interact with others than vulnerable and isolated narcissists. Further research is needed to support these findings. In addition, more insight into the mechanisms underlying these associations is needed to better understand why these three forms of narcissism may be differently associated with relational capacity. Therefore, in this study, we propose two factors that may explain the associations of three narcissistic types (i.e., grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated) with the ability to interact with others.

Identity integration and social concordance as possible explanatory mechanisms

The first factor is identity integration which represents a coherence of identity and the capacity to see oneself and one’s own life as stable, integrated, and purposeful (Verheul et al., 2008). A recent study showed that grandiose narcissism was positively associated with identity integration, while vulnerable narcissism was negatively associated (Bogaerts et al., 2021). It may be that individuals who score high on narcissistic grandiosity have a more integrated identity, as they are more likely to regulate their self-esteem through overt self-enhancement and devaluation of others. Hence, their self-image is less dependent on the perceptions of others (Malkin, 2016). In contrast, the sense of identity of individuals high on narcissistic vulnerability largely depends on the opinions of others, making them hypersensitive to negative feedback from others (Zeigler-Hill et al., 2008). With regard to isolated narcissism, there is no empirical evidence on how it relates to identity integration. However, a stronger sense of coherence has often been associated with lower levels of social isolation (Chu et al., 2016; Limarutti et al., 2021). Thus, because of their tendency to distance themselves from others, isolated narcissists might be expected to have a less integrated identity. Furthermore, integrated identity plays an important role in interpersonal relationships; it is one of the precursors of authentic intimacy with another person. Only individuals with a firm and coherent sense of identity can participate in close, warm, communicative, and committed interactions (Beyers & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010; Bogaerts et al., 2004; Keybollahi et al., 2012; Ragelienė, 2016). Someone with high self-differentiation is better able to form and maintain interpersonal relationships (Rassart et al., 2012) and is less controlling (Adams et al., 1984). Besides, individuals with higher levels of identity integration perceive social interactions as safer and have better quality of peer relationships, more satisfying romantic relationships, and fewer feelings of loneliness (Bogaerts et al., 2006; Doumen et al., 2012). Conversely, individuals with lower levels of identity integration have a chaotic sense of self, unrealistic self-esteem, and unstable perceptions of self and others. As a result, they are less able to integrate positive and negative aspects of images of self and others, which can lead to difficulties in intimate relationships (Di Pierro et al., 2018). It has recently been shown that a disintegrated identity can also lead to violent behavior, but only via self-control. That is, individuals with low levels of identity integration may have a diminished capacity for self-control, making them more prone to criminal behavior (Bogaerts et al., 2021). Taken together, it could be that grandiose narcissists have a superior capacity to relate to others because of their more integrated identity compared to vulnerable and isolated narcissists. To our knowledge, no previous studies to date have investigated whether identity integration can underly the associations of grandiose, vulnerable and isolated narcissism, with relational capacity.

A second factor that may explain why grandiose narcissists have better relational capacities than vulnerable and isolated narcissists is social concordance. Social concordance is defined as the ability to control aggressive impulses toward others, deal with frustration, cooperate well with others, and value and honor others (Verheul et al., 2008). We argue that grandiose narcissists will display higher levels of social concordance compared to vulnerable and isolated narcissists. There is ample evidence that individuals high in grandiose narcissism are more able to control and regulate their emotions (e.g., Casale et al., 2019; Czarna et al., 2021) and show less distrust and hostility towards others (e.g., Czarna et al., 2021; Krizan & Johar, 2015) compared to vulnerable narcissists. It is also believed that vulnerable narcissists are less cooperative due to their hostility and poor anger management, while isolated narcissists are self-preoccupied and do not care much about others (Ettema & Zondag, 2002). One study found that individuals with high narcissistic vulnerability were less likely to cooperate in the prisoner’s dilemma game — used to investigate competitive versus cooperative behavior — and were less likely to initiate or respond to collaboration as the game progressed (Malesza, 2020). They also care less about supporting others, while expecting others to support them (Miller et al., 2011; Pincus et al., 2009). Unlike vulnerable narcissists, grandiose narcissists were more likely to make a good first impression and maintain collaborative relationships (Casale et al., 2019; Malesza, 2020). However, their likeability and willingness to cooperate decreased as the game proceeded. It is plausible that individuals with high grandiose narcissism use cooperation as a strategy to boost their self-esteem, at least at the beginning of the game and until the game moves in the desired direction (Malesza, 2020).

Furthermore, lower levels of social concordance can also impact the quality of interpersonal relationships and lead to poor relations with others. In other words, the inability to control emotions and anger contributes to interpersonal problems and social maladjustment (e.g., Brackett et al. 2006; Caspi et al., 1987). Emotional stability can instead help people avoid fruitless conflicts or mitigate the negative impact of personal antagonisms (Lopes et al., 2011). Likewise, the willingness to cooperate supports the functioning of a wide variety of relationships, including couples (Murray & Holmes, 2009), groups (Fehr et al., 2002), and societies in general (Nowak, 2006). Finally, treating others with dignity and respect presages the ability to give and receive love and build relationships based on mutual caring and trust. Overall, higher levels of social concordance may account for a better capacity to relate with others in individuals high in narcissistic grandiosity. Note that grandiose narcissists rely heavily on others to bolster and maintain their self-esteem. As a result, they engage in behaviors that provide immediate gratification to their desires for social status, positive affect, and ego involvement in achievement domains. However, their actions usually have long-term negative consequences (Jones & Paulhus, 2011; Malesza & Ostaszewski, 2016). Compared to grandiose narcissists, vulnerable narcissists may have less relational capacities due to their lack of cooperation and a tendency to exhibit hostile and aggressive behavior towards others. Similarly, isolated narcissists may have less relational capacities due to their preoccupation with themselves and disinterest in reaching others. Nevertheless, the mediating effect of social concordance in the associations of grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated narcissism with relational capacity has never been tested before.

Present study

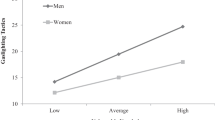

The present study sought to bridge these gaps in the literature by investigating whether identity integration and social concordance can mediate the associations of grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated narcissism with relational capacity. Because our sample includes individuals convicted of criminal behavior as well as individuals from the community and is considerably heterogeneous in terms of age, we included age and belonging to a criminal or community group as controlling variables in the proposed mediation model. In addition, the data further suggest that relational capacity increases with age and therefore it is important to consider age when researching this variable (e.g., Kotiuga et al., 2022). Several hypotheses have been formulated on the basis of the aforementioned literature. First, we hypothesized that grandiose narcissism would have a direct positive effect on relational capacity (e.g., Campbell et al., 2006; Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Vonk et al., 2013; path c1), while vulnerable (e.g., Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; path c2) and isolated narcissism (e.g., Ettema & Zondag, 2002; path c3) would have a direct negative effect on relational capacity. In line with the recent study (Bogaerts et al., 2021) we further hypothesized that grandiose narcissism would have a direct positive effect (path a11), while vulnerable narcissism would have a direct negative effect (path a21) on identity integration. There is no empirical evidence on the effect of isolated narcissism on identity integration, but given that isolated narcissists tend to distance themselves and that lower levels of social isolation were found to be associated with a stronger sense of coherence (Chu et al., 2016; Limarutti et al., 2021), we expected that isolated narcissism like vulnerable narcissism, would have a direct negative effect on identity integration (path a31). Similarly, we hypothesized that grandiose narcissism (e.g., Casale et al., 2019; Czarna et al., 2021; path a12) would have a direct positive effect, whereas vulnerable (e.g., Krizan & Johar, 2015; path a 22) and isolated narcissism (Ettema & Zondag, 2002; path a32) would have a direct negative effect on social concordance. Consistent with previous evidence, we expected that both identity integration (e.g., Beyers & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010; Keybollahi et al., 2012; path b1) and social concordance (Fehr et al., 2002; Murray & Holmes, 2009; path b2) would have a direct positive effect on relational capacity. Finally, based on the discussed literature, we argue that grandiose narcissists would have a better capacity to relate to others, probably due to their better sense of self and lower hostility and better cooperative skills. Therefore, we hypothesized that identity integration and social concordance would be significant mediators in the positive association between grandiose narcissism and relational capacity, and the negative association of vulnerable and isolated narcissism with relational capacity. See Fig. 1, for a graphical representation of the model.

Shedding light on the mechanisms underlying the associations of these three narcissistic types with relational capacity could benefit the treatment of narcissistic individuals and potentially make them less harmful to others in social and intimate relationships.

Methods

Participants and procedure

This study is part of a larger research project investigating personality and relationships among participants from both forensic psychiatric institutions and the community. The sample comprised 222 male participants. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 60, with a mean age of 37.71 years (SD = 13.25). Most of the participants self-reported a Dutch nationality (67.6%, n = 150), living alone (28.2%, n = 62), and having an income from paid employment (65.4%, n = 138). The most common finished level of education was intermediate vocational education/MBO (31.1%, n = 69), followed by higher professional education/HBO (28.4%, n = 63), higher general secondary education/HVO (9%, n = 20), and secondary education/VWO (9%, n = 20). Of this sample, 157 (70.7%) were participants from the community and 65 (29.3%) were outpatients in treatment at four Dutch outpatient forensic centers. Forensic patients were attending mandatory treatment which was imposed by the judge due to a committed offense. The index offenses included physical aggression (45.3%, n = 29); domestic violence (31.3%, n = 20); verbal aggression (20.3%, n = 13); and other offenses (3.1%, n = 10). More details on sample characteristics can be found in Table A1 in the appendix.

All participants were introduced to the purpose of the study and gave written informed consent to take a voluntary part. They did not receive any payment or other benefits for their participation and were informed that participation may be discontinued at any time without penalty or loss. Participants from forensic centers were also informed that their decision to participate in the study would not have any influence on their treatment status, and that information gathered for this research would not be shared with their therapists. Forensic patients completed questionnaires during a treatment session. Furthermore, master-level students in clinical forensic psychology recruited the participants from the community by a means of a snowball sampling technique. Snowball sampling is a non-probability sampling technique where currently enrolled research participants assist researchers in identifying other potential participants. Inclusion criteria included being at least 18 years old and having sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language. Community participants were matched with the participants convicted of criminal behavior on two characteristics, namely age and level of education. Participants with a university degree were excluded from the community sample because this category was not present in the sample of criminals. To ensure that community participants did not belong to the criminal group, they were asked if they had ever been convicted of a criminal offense. In addition, community participants who had been in treatment with a psychologist, psychotherapist, or another care provider in the past three years were excluded. None of the community respondents reported a history of criminal behavior or a history of counseling. All participants were instructed to return the completed questionnaires in a sealed envelope. The data were anonymized and could not be traced to an individual participant. All procedures involving human participants were performed according to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Scientific Research Committee of FPC Kijvelanden and the Ethical Review Board of Tilburg University approved the study.

Measures

Grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated narcissism

The Dutch Narcissism Scale ([Nederlandse Narcisme Schaal]; NNS; Ettema & Zondag, 2002) was used to measure grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated narcissism. The 35-item NNS is a Dutch adaptation of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (Raskin & Hall, 1979, 1981) and the Hypersensitive Narcissism scale (Hendin & Cheek, 1997). It is a self-report questionnaire measuring three different types of narcissism including vulnerable narcissism (11 items; e.g., “Small remarks of others can sometimes easily hurt my feelings”), grandiose narcissism (12 items; “Sometimes I feel like I got lucky with who I am anyway”) and isolation (12 items; “I often have the feeling that there is a shield separating me from others”; Ettema & Zondag, 2002). All items are rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = that is certainly not the case to 7 = that is certainly the case. The total scores were computed for each narcissism subscale by summing all the items that belonged to the corresponding subscale. Higher scores indicate greater levels of narcissism. The validity of the Dutch NNS was demonstrated by its relations with age, self-esteem, burnout, and empathy (Ettema & Zondag, 2002), the meaning of life (Zondag, 2005), satisfaction with life and depression (Nauta & Derckx, 2007), and boredom (Zondag, 2007). In previous research, internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of grandiose narcissism ranged from 0.71 to 0.77, and of vulnerable narcissism from 0.77 to 0.87. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.71 for grandiose narcissism, 0.81 for vulnerable narcissism and 0.78 for isolated narcissism.

Identity integration, social Concordance, and relational capacity

The Severity Indices of Personality Problems – Short Form (SIPP-SF; Verheul et al., 2008) was used to measure identity integration, social concordance, and relational capacity. The SIPP-SF is a 60-item self-report questionnaire that measures five domains of maladaptive personality functioning, namely: self-control (12 items), identity integration (12 items), relational capacities (12 items), responsibility (12 items), and social concordance (12 items). All items are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = fully disagree to 4 = fully agree, with higher scores indicating greater impairments. The self-control and responsibility domains of the SIPP-SF were not included in this study. The identity integration domain (e.g., “I strongly believe that I am just as worthy as other people”) captures the capacity to see oneself and one’s own life as stable, integrated, and purposive. The social concordance domain (e.g., “I can work with people on a joint project in spite of personal differences”) captures the capacity to value someone’s needs and identity, resist aggressive impulses towards others, and work together with others. The relational capacity domain (e.g., “I have been able to form lasting friendships”) captures the capacity to genuinely care about others and to feel loved and recognized by others, as well as the ability to share mutual experiences with others often but not necessarily in the context of a long-term, intimate relationship. Total scores were calculated for each of these three domains by summing all items that belonged to that domain. Higher scores indicated higher levels of identity integration, social concordance or relational capacity. The SIPP-SF has demonstrated good psychometric properties in both Dutch and English samples (Arnevik et al., 2009; Rossi et al., 2017). In the current sample, all three domains have shown very good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 (identity integration), 0.85 (social concordance) and 0.87 (relational capacity).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25) and free software environment R (R Core Team, 2021). First, descriptive statistics were computed to summarize sample characteristics. Subsequently, the point-biserial correlation was used to measure the relationship between the continuous and a binary variable (i.e., criminal behavior), while the Pearson correlation was used to measure the relationship between pairs of continuous variables. Criminal behavior was used as the grouping variable where 0 = community participants and 1 = sample of criminals (i.e., a conviction of one or more violent crimes). Finally, we used the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012) to test whether identity integration and social concordance mediate the association of grandiose, vulnerable and isolated narcissism with relational capacity, controlled for age and belonging to a criminal or community group through path analysis. Path analysis can be seen as a special case of structural equation modeling and involves only observable variables (Lei & Wu, 2007). We applied the maximum likelihood method to assess parameter estimates. In addition, the fit of the model was evaluated with the comparative fit index (CFI; values ≥ 0.90) and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; <0.08; Hu and Bentler, 1999). Before the analyses, it was checked whether the data are normally distributed. Data are normally distributed if absolute values of skewness and kurtosis are not larger than 2 (Field, 2009).

Results

Descriptive statistics, including skewness and kurtosis, are presented in Table 1. All variables were normally distributed. Table 2 depicts the point-biserial and Pearson correlations. Relational capacity positively correlated with grandiose narcissism, identity integration and social concordance, respectively, and negatively correlated with vulnerable narcissism, isolated narcissism and criminal behavior. In addition, grandiose narcissism had a positive correlation with identity integration and social concordance, while vulnerable and isolated narcissism had negative correlations with these variables.

The results of the mediation analysis are summarized in Table 3. The model fitted the data well (CFI = 0.94 and SRMR = 0.05). Considering direct effects, isolated narcissism (b = − 0.24, p < .001), and criminal behavior (b = − 2.30, p = .01) were negatively associated with relational capacity, while identity integration (b = 0.38, p < .001), and social concordance (b = 0.016, p = .01) were positively associated with relational capacity. Grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism and age did not have a significant association with relational capacity. Furthermore, grandiose narcissism was positively (b = 0.32, p < .001), whereas vulnerable (b = − 0.10, p = .03) and isolated narcissism (b = − 0.37, p < .001) were negatively associated with identity integration. Finally, grandiose narcissism had a positive association (b = 0.09, p = .03), while isolated narcissism (b=- 0.33, p < .001) had a negative association with social concordance. Vulnerable narcissism was not significantly associated with social concordance.

When it comes to indirect effects, grandiose narcissism was significantly and positively associated with relational capacity through identity integration (b = 0.12, p < .001), while social concordance was not a significant mediator in this association. This means that a higher level of grandiose narcissism leads to a more coherent identity which in turn enhances the capacity to relate with others. Likewise, identity integration (b = − 0.03, p = .03) was a significant mediator in the negative association between vulnerable narcissism and relational capacity, whereas social concordance did not have a significant mediating role in this association. This indicates that individuals high in vulnerable narcissism have a less coherent sense of self which further negatively influences their relations with others. In contrast, both identity integration (b = − 0.014, p < .001) and social concordance (b = − 0.05, p = .01) significantly mediated the negative association between isolated narcissism and relational capacity. This finding signifies that a higher level of isolated narcissism leads to a less coherent identity and lower social concordance which consequently results in lower relational capacity.

Discussion

Despite the well-established multidimensional nature of narcissism, the association between narcissism as a multidimensional construct and the capacity to relate with others has never been tested before. In this study, we investigated how three different types of narcissism, namely grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated, are associated with relational capacity in 222 males from the community and forensic population. In addition, it was also investigated whether identity integration and social concordance may underly these associations. The proposed mediation model was tested in R and the analysis was adjusted for age and belonging to a criminal or community group. The results revealed that of the three narcissistic types, only isolated narcissism had a direct effect on relational capacity, while criminal behavior was the only significant covariate. In addition, both identity integration and social concordance had a positive direct effect on relational capacity. Furthermore, grandiose (+) and vulnerable narcissism (-) were significantly associated with relational capacity only through identity integration, while social concordance was not a significant mediator in this association. In contrast, both identity integration and social concordance significantly mediated the negative association between isolated narcissism and relational capacity.

Consistent with our hypothesis, individuals with higher levels of isolated narcissism showed a poorer capacity to relate with others. Isolated narcissists seem to be less capable of really caring about other people and sharing mutual experiences with them. This can be explained by their excessive narcissistic need for self-preoccupation and beliefs that others cannot recognize and understand their worth (Ettema & Zondag, 2002). However, we found no significant direct associations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism with relational capacity. Grandiose narcissism did have a significant positive correlation with relational capacity, while vulnerable narcissism had a negative correlation. Previous research has shown that narcissistic grandiosity is associated with less avoidance within interpersonal relationships (Campbell et al., 2006; Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Rohmann et al., 2012) and also with higher levels of perspective-taking, emotional intelligence, social reasoning, and empathy (Vonk et al., 2013); all these factors are assumed to positively influence social interactions. In contrast, narcissistic vulnerability is associated with greater social withdrawal, feelings of insecurity, and concern about possible rejection (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Rohmann et al., 2012; Smolewska & Dion, 2005), that is, the factors that may harm relations with others. In this study, we cannot make any statements about the direction of these significant associations of the two types of narcissism with a relational capacity based on correlations. Based on our empirical findings, our results provide some empirical support for the evidence that individuals with higher levels of grandiose narcissism are better able to get along with others in comparison to individuals with higher levels of vulnerable narcissism. The absence of significant direct effects of the two types of narcissism on relational capacity may be because we included identity integration and social concordance as mediators in the model. Given the significant bivariate correlations between the two different forms of narcissism and mediators, the lack of significant direct effects could therefore be explained by the common variance shared by these variables.

Indeed, in line with our hypotheses, identity integration explained the positive association between grandiose narcissism and relational capacity, as well as the negative association of vulnerable and isolated narcissism with relational capacity. This finding suggests that individuals high on grandiose narcissism have a more coherent sense of self and thus a better capacity to relate with others. This is consistent with previous findings showing that individuals with higher levels of grandiose narcissism have a better-integrated identity (Bogaerts et al., 2021). It also supports the idea that identity integration can be seen as a precursor to authentic intimacy with another person and that only individuals with high self-differentiation are able to form warm and close interpersonal relationships (Beyers & Seiffge-Krenke, 2010; Keybollahi et al., 2012; Rassart et al., 2012). In contrast, our results indicate that individuals high in narcissistic or isolated vulnerability have a less coherent identity, which may ultimately reduce their capacity to relate with others. The previous study also found that vulnerable narcissists have a chaotic sense of self and unstable perceptions of self and others (Bogaerts et al., 2021). Lower levels of identity integration of individuals with high narcissistic vulnerability were attributed to their enhanced sensitivity to negative feedback from others (Rogoza et al., 2018; Zeigler-Hill et al., 2008). Individuals with a disintegrated identity thus have more difficulty integrating positive and negative representations of self and others, which makes them less able to interact with others (Di Pierro et al., 2018) and makes them more prone to criminal behavior along with isolated narcissists (Bogaerts et al., 2021). Similarly, isolated narcissists may have a less integrated identity due to their increased need for social isolation (Chu et al., 2016; Limarutti et al., 2021). In brief, in addition to supporting existing findings, our study provides direct evidence that identity integration may explain why vulnerable and isolated narcissists have a lower capacity to relate to others than grandiose narcissists.

The present study also provides evidence that not only identity integration, but also social concordance may be an explanatory mechanism in the negative association between isolated narcissism and relational capacity. Individuals high in narcissistic isolation are less able to appreciate the needs of others, resist aggressive impulses towards others, and cooperate with others. This can lead to interpersonal problems and social maladjustment (e.g., Brackett et al. 2006; Caspi et al., 1987). Contrary to our expectations, this study did not support the mediating effect of social concordance on the association between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and relational capacity. It could be that social concordance was only a significant mediator in the association between isolated narcissism and relational capacity because isolated narcissists hold considerably more negative views of others than the other two types of narcissism. Specifically, grandiose narcissists only see others as a means to bolster their self-image (Pincus et al., 2014), while vulnerable narcissists tend to perceive others mainly as a threat to their fragile ego (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Pincus et al., 2009). In contrast, isolated narcissists have beliefs that others are overly critical of them, that they do not value their worth, and that they cannot be fully understood and valued by others (Ettema & Zondag, 2002). All these extremely negative views of other people can cause isolated narcissists to constantly withdraw from others and have more difficulty controlling their negative impulses toward others, making it more difficult for them to relate to others.

Furthermore, our findings also fit with previous studies showing that grandiose narcissism is a better-adapted narcissistic subtype than vulnerable or isolated narcissism (e.g., Ettema & Zondag, 2002; Kaufman et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2014; Rose, 2002). For example, previous research has linked grandiose narcissism to better life satisfaction, lower perceived stress (Ng et al., 2014), a tendency toward assertiveness, persistence, and achievement (Rose, 2002), and non-criminality (Bogaerts et al., 2021). Our research also showed that, as opposed to vulnerable or isolated narcissism, grandiose narcissism is associated with better identity integration, higher levels of social concordance, and a greater capacity to relate with others. Although these grandiose narcissists may seem more satisfied with their lives and more capable of interacting with others, their “good” intentions are usually manipulative and connected to their endless identity needs for superiority (Jonason & Webster, 2012. Hence, their actions usually have negative consequences for other people in the long run (Jones & Paulhus, 2011; Malesza & Ostaszewski, 2016).

Limitations and future direction

This study is not without limitations. We only included males and therefore the results cannot be generalized to females. In addition, we used the snowball sampling method to recruit participants from the community. Thus, the representativeness of the subsample of the controls cannot be guaranteed. Another limitation concerns the validity of our findings relying solely on self-reported data. It has been suggested that self-reported data can be influenced by external biases such as social desirability. Offenders are particularly thought to employ socially desirable responding styles (Mills & Kroner, 2006) and for this reason, we cannot rule out the possibility that reported results are partly influenced by intentional deception in our sample. Finally, when adjusting the analysis for the age and belonging to the criminal or community group, due to the small sample size, we considered only the adjustments related to the outcome variable, although these covariates could affect the other variables in the model as well. For example, it has been shown that narcissism is overrepresented in individuals convicted of criminal offenses as well as that it tends to decline with age (Foster et al., 2003). Future studies should therefore attempt to include a more representative and larger sample of both genders and intend to measure the constructs of interests more objectively, via direct observations as well as to control all variables in the model for the potential influence of age and criminal behavior.

Nevertheless, the findings of the present study could be of practical importance for enhancing the relational competence of grandiose, vulnerable, and isolated narcissists. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were not directly, but only indirectly related to relational capacity via identity integration. Thus, the intervention aimed at improving the relational capacity of individuals high on narcissistic grandiosity or vulnerability should focus on developing a more coherent identity. Similarly, for isolated narcissists, a successful relational intervention should focus on strengthening both identity integration and social concordance as they were significant in explaining mechanisms of diminished capacity to relate with others for this particular type of narcissist. Thus, by enhancing these two, it is highly likely that relational capacity would be improved as well.

To conclude, the present study adds to the understanding of how three different types of narcissism are associated with relational capacity as well as to what extent identity integration and social concordance could explain these associations. Consistent with the literature, grandiose narcissism can be viewed as a healthier type of narcissism compared to the other two types. In addition, the findings of this study may hold important clinical implications. However, before translating the findings of this study into practice, replication studies are necessary to confirm our results.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adams, G. R., Ryan, J. H., Hoffman, J. J., Dobson, W. R., & Nielsen, E. C. (1984). Ego identity status, conformity behavior, and personality in late adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(5), 1091–1104. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.47.5.1091

Arnevik, E., Wilberg, T., Monsen, J. T., Andrea, H., & Karterud, S. (2009). A cross-national validity study of the severity indices of personality problems (SIPP‐118). Personality and Mental Health, 3(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.60

Aradhye, C., & Vonk, J. (2014). Theory of mind in vulnerable and grandiose narcissism. Psychology of emotions, motivations and actions. Handbook of the psychology of narcissism: Diverse perspectives, 347–361.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the mind in the Eyes” test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 42(2), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00715

Barelds, D. P., Dijkstra, P., Groothof, H. A., & Pastoor, C. D. (2017). The Dark Triad and three types of jealousy: Its’ relations among heterosexuals and homosexuals involved in a romantic relationship. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.017

Beyers, W., & Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2010). Does identity precede intimacy? Testing Erikson’s theory on romantic development in emerging adults of the 21st century. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25(3), 387–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0743558410361370

Bogaerts, S., Garofalo, C., De Caluwé, E., & Janković, M. (2021). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, identity integration and self-control related to criminal behavior. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00697-1

Bogaerts, S., Vanheule, S., & Desmet, M. (2006). Feelings of subjective emotional loneliness: An exploration of attachment. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 34(7), 797–812. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2006.34.7.797

Bogaerts, S., Vervaeke, G., & Goethals, J. (2004). A comparison of relational attitude and personality disorders in the explanation of child molestation. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SEBU.0000006283.30265.f0

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., & Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

Casale, S., Rugai, L., Giangrasso, B., & Fioravanti, G. (2019). Trait-emotional intelligence and the tendency to emotionally manipulate others among grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. The Journal of Psychology, 153(4), 402–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1564229

Caspi, A., Elder, G. H., & Bem, D. J. (1987). Moving against the world: Life-course patterns of explosive children. Developmental Psychology, 23(2), 308.

Campbell, W. K., Brunell, A. B., & Finkel, E. J. (2006). Narcissism, interpersonal Self-Regulation, and romantic Relationships: An Agency Model Approach. In K. D. Vohs, & E. J. Finkel (Eds.), Self and relationships: Connecting intrapersonal and interpersonal processes (pp. 57–83). The Guilford Press.

Czarna, A. Z., Zajenkowski, M., Maciantowicz, O., & Szymaniak, K. (2021). The relationship of narcissism with tendency to react with anger and hostility: The roles of neuroticism and emotion regulation ability. Current Psychology, 40(11), 5499–5514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00504-6

Chin, K., Atkinson, B. E., Raheb, H., Harris, E., & Vernon, P. A. (2017). The dark side of romantic jealousy. Personality and Individual Differences, 115, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.003

Chu, J. J., Khan, M. H., Jahn, H. J., & Kraemer, A. (2016). Sense of coherence and associated factors among university students in China: Cross-sectional evidence. BMC public health, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3003-3

Cooper, A. (1981). Narcissism. In S. Arieti, H. Keith, & H. Brodie (Eds.), American Handbook of Psychiatry (4 vol., pp. 297–316). New York: Basic Books.

Cooper, A. (1998). Further developments in the clinical diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder. In E. Ronningstam (Ed.), Disorders of narcissism: Diagnostic, clinical, and empirical implications (pp. 53–74), Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(3), 188–207. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.3.188.22146

Di Pierro, R., Di Sarno, M., Preti, E., Di Mattei, V. E., & Madeddu, F. (2018). The role of identity instability in the relationship between narcissism and emotional empathy. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 35(2), 237. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000159

Doumen, S., Smits, I., Luyckx, K., Duriez, B., Vanhalst, J., Verschueren, K., & Goossens, L. (2012). Identity and perceived peer relationship quality in emerging adulthood: The mediating role of attachment-related emotions. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1417–1425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.01.003

Ettema, J. H. M., & Zondag, H. J. (2002). De Nederlandse Narcisme Schaal (NNS): Psychodiagnostisch gereedschap [The dutch scale of Narcissism]. Psycholoog, 37(5), 250–255.

Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., & Gächter, S. (2002). Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms. Human Nature, 13(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-002-1012-7

Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 3rd Edition, Sage Publications Ltd., London.

Foster, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Twenge, J. M. (2003). Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00026-6

Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray’s Narcism Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588–599.

Hepper, E. G., Hart, C. M., Meek, R., Cisek, S., & Sedikides, C. (2014). Narcissism and empathy in young offenders and non–offenders. European Journal of Personality, 28(2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/2Fper.1939

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2012). A protean approach to social influence: Dark Triad personalities and social influence tactics. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(4), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.023

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2011). The role of impulsivity in the Dark Triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(5), 679–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.011

Kaufman, S. B., Weiss, B., Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2020). Clinical correlates of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism: A personality perspective. Journal of Personality Disorders, 34(1), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2018_32_384

Kernberg, O. (1967). Borderline Personality Organization. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 15(3), 641–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306516701500309

Keybollahi, T., Mansoobifar, M., & Mujembari, A. K. (2012). The relationship between identity statuses and attitudes toward intimately relations considering the gender factor. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 899–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.220

Kotiuga, J., Yampolsky, M. A., & Martin, G. M. (2022). Adolescents’ perception of their sexual self, relational capacities, attitudes towards sexual pleasure and sexual Practices: A descriptive analysis. Journal of youth and adolescence, 51(3), 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01543-8

Krizan, Z., & Johar, O. (2015). Narcissistic rage revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(5), 784. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000013

Larson, M., Vaughn, M. G., Salas-Wright, C. P., & Delisi, M. (2015). Narcissism, low self-control, and violence among a nationally representative sample. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(6), 644–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0093854814553097

Lei, P. W., & Wu, Q. (2007). Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 26(3), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2007.00099.x

Limarutti, A., Maier, M. J., & Mir, E. (2021). Exploring loneliness and students’ sense of coherence (S-SoC) in the university setting. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02016-8

Lopes, P. N., Nezlek, J. B., Extremera, N., Hertel, J., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Schütz, A., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotion regulation and the quality of social interaction: Does the ability to evaluate emotional situations and identify effective responses matter? Journal of Personality, 79(2), 429–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00689.x

Malesza, M. (2020). Grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism in prisoner’s dilemma game. Personality and Individual Differences, 158, 109841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109841

Malesza, M., & Ostaszewski, P. (2016). Dark side of impulsivity—Associations between the Dark Triad, self-report and behavioral measures of impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.016

Malkin, C. (2016). Rethinking narcissism: The secret to recognizing and coping with narcissists. Harper Perennial.

Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism. Journal of Personality, 76(3), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00492.x

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Campbell, K., W (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x

Mills, J. F., & Kroner, D. G. (2006). Impression management and self-report among violent offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0886260505282288

Murray, S. L., & Holmes, J. G. (2009). The architecture of interdependent minds: A motivation-management theory of mutual responsiveness. Psychological Review, 116(4), 908. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017015

Nauta, R., & Derckx, L. (2007). Why sin?—A test and an exploration of the social and psychological context of resentment and desire. Pastoral Psychology, 56(2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-007-0097-7

Ng, H. K., Cheung, R. Y. H., & Tam, K. P. (2014). Unraveling the link between narcissism and psychological health: New evidence from coping flexibility. Personality and Individual Differences, 70, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.06.006

Nowak, M. A. (2006). Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science, 314(5805), 1560–1563. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1133755

Pincus, A. L., Cain, N. M., & Wright, A. G. C. (2014). Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability in psychotherapy. Personality Disorders: Theory Research and Treatment, 5(4), 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000031

Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G. C., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016530

Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), 590. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590

Raskin, R., & Hall, C. S. (1981). The narcissistic personality inventory: Alternative form reliability and further evidence of construct validity. Journal of Personality Assessment, 45(2), 159–162. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4502_10

Ragelienė, T. (2016). Links of adolescents identity development and relationship with peers: A systematic literature review. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(2), 97.

Rassart, J., Luyckx, K., Apers, S., Goossens, E., Moons, P., & i-DETACH Investigators. (2012). Identity dynamics and peer relationship quality in adolescents with a chronic disease: The sample case of congenital heart disease. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 33(8), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP

R Core Team (2021). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.r-project.org

Rogoza, R., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Kwiatkowska, M. M., & Kwiatkowska, K. (2018). The bright, the dark, and the blue face of narcissism: The spectrum of narcissism in its relations to the metatraits of personality, self- esteem, and the nomological network of shyness, loneliness, and empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00343

Rose, P. (2002). The happy and unhappy faces of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(3), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00162-3

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36.

Rossi, G., Debast, I., & Van Alphen, S. P. J. (2017). Measuring personality functioning in older adults: Construct validity of the severity indices of personality functioning–short form (SIPP-SF). Aging & Mental Health, 21(7), 703–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1154012

Rohmann, E., Neumann, E., Herner, M. J., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2012). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. European Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000100

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 400. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400

Smolewska, K., & Dion, K. (2005). Narcissism and adult attachment: A multivariate approach. Self and Identity, 4(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000218

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2009). The narcissism epidemic: Living in the age of entitlement. Simon and Schuster.

Verheul, R., Andrea, H., Berghout, C. C., Dolan, C., Busschbach, J. J. V., van der Kroft, P. J. A., Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2008). Severity indices of personality problems (SIPP-118): Development, factor structure, reliability, and validity. Psychological Assessment, 20(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/10403590.20.1.23

Vonk, J., Zeigler-Hill, V., Mayhew, P., & Mercer, S. (2013). Mirror, mirror on the wall, which form of narcissist knows self and others best of all? Personality and Individual Differences, 54(3), 396–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.010

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590

Zeigler-Hill, V., Clark, C. B., & Pickard, J. D. (2008). Narcissistic subtypes and contingent self‐esteem: Do all narcissists base their self‐esteem on the same domains? Journal of Personality, 76(4), 753–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00503.x

Zondag, H. (2005). Between imposing one’s will and protecting oneself. Narcissism and the meaning of life among dutch pastors. Journal of Religion and Health, 44(4), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-005-7180-0

Zondag, H. J. (2007). Introductie van een Nederlandstalige Schaal voor Gevoelligheid voor Verveling ([Introduction of a dutch scale for boredom and susceptibility] NSGV). Psychologie & Gezondheid, 35(5), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03071803

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [Stefan Bogaerts], and [Marija Janković]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Stefan Bogaerts] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

All procedures involving human participants were performed according to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Scientific Research Committee of FPC Kijvelanden and the Ethical Review Board of Tilburg University approved the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix head

Appendix head

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bogaerts, S., Janković, M. Narcissism and relational capacity: the contribution of identity integration and social concordance. Curr Psychol 43, 3915–3927 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04622-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04622-0