The history of Filipinos and black Americans overlap in surprising ways. Contemporary discourse has drawn comparisons between incidents of police brutality here and in the US, and are a point of solidarity. But roots of this solidarity run deeper than that. Filipinos and Black Americans have before found themselves crossing paths in another violent time—specifically the Philippine-American War of 1899 and 1902.

Manila House recently held a panel on this understudied fragment of history called A Conflict of Conscience: Buffalo Soldiers in the Philippine-American War. Moderated by Bambina Olivares, the panel was attended by a roster of accomplished academics: filmmaker Mark Harris, historians Anthony Powell, Frank Schubert and Vicente Rafael, law expert Gill Boehringer, academic Rik Penn, and Evangeline Canonizado Buell, an author and Filipino direct descendant of a buffalo soldier. The discussion was anchored in many ways by Harris, who is in the middle of working on a documentary called, well, “A Conflict of Conscience,” on the panel’s subject of interest.

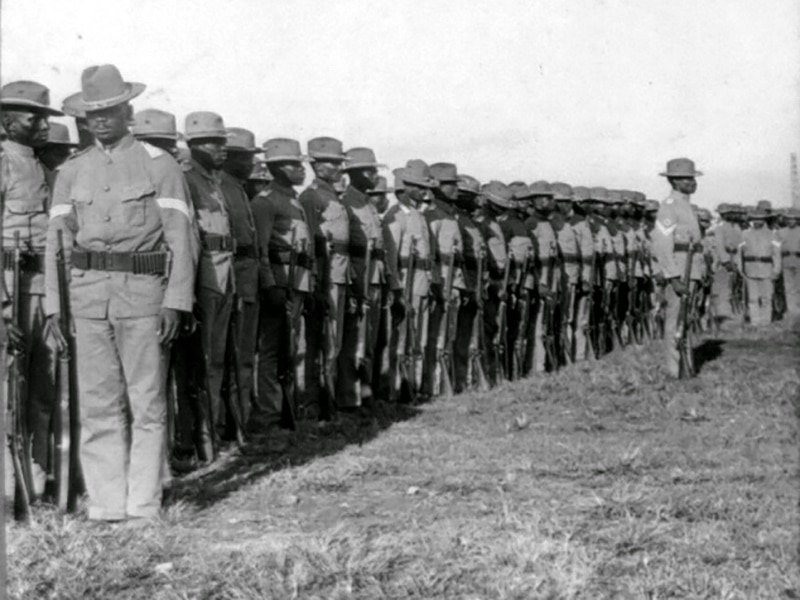

The panel began with Mark Harris giving a general introduction on the black soldiers of the war. The term “buffalo soldier” originated from Native Americans, who remarked that the hair of black soldiers reminded them of buffalo fur. These soldiers were either slaves or the sons of former slaves. And while the Philippine-American war came a few decades after the abolishment of slavery in the United States, this was still a tumultuous time in racist America.

According to Rafael, by August of 1898, Filipinos were just about to take Manila back from the Spaniards and become a full-fledged politically sovereign country, but something got in the way. “Just as when the Filipinos were poised to take Manila and complete their victories, the United States forces came in and basically forced them out of their positions. The US made a deal with the Spaniards, conducting a quote unquote mock battle of Manila Bay, so that the Spaniards refused to surrender to the Filipinos. The Americans kept Filipinos out from occupying Manila. And by August 13, the Americans were able to occupy the seat of the former colonial government.”

Believing that Filipinos weren’t ready for self-rule, the Americans occupied our territories, and targeted insurgents and civilian supporters. As Rafael put it, “the war was racialized.”

Here is where the conflict of conscience comes in. Black soldiers enlisted in the US army, who participated in the occupation of the country, were firsthand witnesses to how Americans subjugated Filipinos. These black soldiers saw Filipinos as fellow dark-skinned brothers and sisters, subject to the forms of oppression and violence they faced in the heartland. Both Filipino and black people were called the n-word slur. This prompted an internal conflict among the black soldiers—should they fight the war? Or could they possibly side with these strangers in a strange land, oceans away from the life they used to know?

A letter from a buffalo soldier stationed in the Philippines expresses this personal inner battle. It read: “Every colored soldier who goes to the Philippine Islands to fight the brave men there who are fighting and dying for their freedom… is fighting to curse the country with color-phobia, lynchings, Jim Crow (train)cars, and everything else that white prejudice can do to blight the darker races… and since the Filipinos belong to the darker human variety, it is the Negro fighting against himself.” The infantryman who wrote this letter died three weeks later.

This is the heart of the conflict of conscience. Buffalo soldiers actually did have incentive to fight the war, even if it served a nation that oppressed them. Anthony Powell recalled a conversation that he had with his grandfather, who served 40 years in the army, from 1887 to 1927. “When I was a young buck thinking that I knew everything, I asked my grandfather in the mid-50s, I said, ‘Granddad, why did you serve this racist nation for all of those years?’ And he told me something I’ll never forget. He said the army gave him the only part of the American dream that the nation would let him be in.”

Ths US army gave black Americans the most viable promise of social and economic upward mobility. Because according to Powell, “outside the structure of the army, African-American men did not have much of a chance to improve their lot in life.”

One would do well to remember that in an extremely racist America, black folks had very little options in terms of choosing jobs or going to school. It must also be noted that enlisting in the military actually means that you get an education. Rik Penn mourns, “There has always been a hope amongst African-American civilians and politicians, that by giving a blood sacrifice to the country, this will somehow raise your stature, give you a greater standing, and recognition among the other white civilians. That somehow, this will show them, this will be the thing that will cause that surge of brotherhood, that they will rise above all this racism and be accepted as full class citizens. That continued up into Vietnam.”

Still, there were buffalo soldiers who took all factors into account, including the violence Americans inflicted upon Filipinos, and chose to defect from the military. Frank Schubert discussed the elusive figure David Fagen, a buffalo soldier whose personal life is kind of a mystery, but whose defection was substantially covered and reported. Born in Tampa Florida, Fagen defected to the other side and became a guerilla leader, supposedly after communicating with Filipino revolutionaries. White leadership in the military were obsessed with Fagen and saw him as a traitor. Some reports say that he was brought back dead, while others say he lived the rest of his peaceful life in the mountains of Nueva Ecija.

These are the unlikely encounters, and the relationships produced from them, that we don’t always find in our history textbook, still need to be acknowledged. Gill Boehringer took the time to tell the story of the friendship between US Sergeant John Calloway and his friend Tomas Consunji, who worked for the United States government in the Filipino administration, but was also suspected to be an undercover agent for the Nationalists. They would have dinner together and exchange letters, but their correspondence would lead the US to brand Calloway a potential defector. A paper written by Boehringer goes into detail about the complications of this relationship, and the fate he was dealt under the US justice system.

You may also like:

The panel concluded with Evangeline Canonizado Buell reading an excerpt of her memoir “Twenty-Five Chickens and a Pig for a Bride.” The excerpt spoke of her grandfather Ernest Stokes, a buffalo soldier who responded for a call to volunteers for the war in the Philippines. By forming relationships with the Filipinos around him, he learned to speak Ilocano, Kapampangan, Tagalog, and Bisaya. He married a Filipina by the name of Maria Bunag, and after Bunag passed away, some time would pass before he married again, to Roberta Dungca, whom he met in Pampanga. Stokes even taught his wife to cook soul food from his hometown of Tennessee. It is interesting to think about how these stories of cultural contact spring forth from how minority groups respond to oppression and process their shared experiences.

One can look at the online event as a method of research for Mark Harris, working on the film as we speak. But more importantly, it was an opportunity for Americans and Filipinos alike who virtually attended the event to discuss and share stories, considering how the finer details of the Philippine-American war aren’t discussed in the average history class. In what other unlikely ways have Filipino and black Americans interacted over the course of human history? What insights can be gleaned from these points of contact? Perhaps these insights express one truth: that solidarity, in its simplest sense, means to acknowledge and bond over the things different people have in common. One just has to know where to look. And when we do find them, hopefully it won’t be in wartime.

You can watch the panel on YouTube.