This lesson continues in The Brutality of the Philippine-American War. It is a part of a larger unit on the Philippines: At the Crossroads of the World. It is also written to be utilized independently.

This lesson was reported from:

Adapted in part from open sources.

Philippine Revolution

- In his famous novel El Filibusterismo, describing the abuses the Spanish government and the colonial church, Jose Rizal wrote, “It is a useless life that is not consecrated to a great ideal. It is like a stone wasted in the field without becoming part of an edifice.” What did he mean? Did he achieve this goal in his own life?

- Many risked and ultimately sacrificed their lives and livelihood for the cause of Philippine independence. What cause do you believe in?

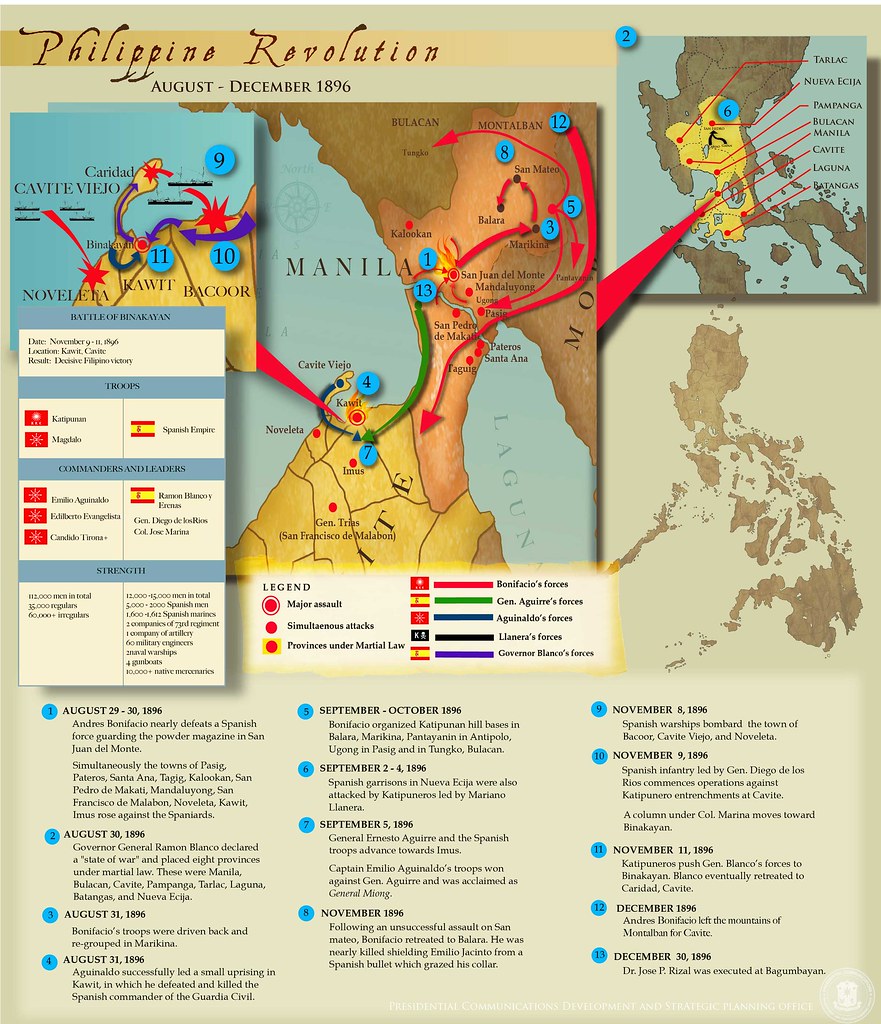

Andrés Bonifacio was a warehouseman and clerk from Manila, fed up with Spanish rule and his status as a second class citizen in his own homeland, and inspired, like many, by the writings of Jose Rizal. He established the Katipunan—a revolutionary organization which aimed to gain independence from Spanish colonial rule by armed revolt—on July 7, 1892. After more than three hundred years of colonial rule, discontent was widespread among the Filipino population, and support for the movement grew quickly. Fighters in Cavite province, across the bay from Manila, won early victories. One of the most influential and popular leaders from Cavite was Emilio Aguinaldo, mayor of Cavite El Viejo, who gained control of much of the eastern portion of Cavite province. Eventually, Aguinaldo and his faction gained control of the leadership of the Katipunan movement. Aguinaldo was elected president of the Philippine revolutionary movement at the Tejeros Convention on March 22, 1897, and Bonifacio was executed for treason by Aguinaldo’s supporters after a show trial on May 10, 1897.

Aguinaldo’s exile and return

- Why did Aguinaldo agree to leave the Philippines? Do you agree with his decision?

- What was the decisive contribution of the Americans to the defeat of the Spanish?

- Was Aguinaldo’s right to claim independence for the Philippines legitimate?

By late 1897, after a succession of defeats for the revolutionary forces, the Spanish had regained control over most of the Philippines. Aguinaldo and Spanish Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera entered into armistice negotiations. On December 14, 1897, an agreement was reached in which the Spanish colonial government would pay Aguinaldo $800,000 Mexican pesos—which was approximately equivalent to $400,000 United States dollars at that time in Manila—in three installments if Aguinaldo would go into exile outside of the Philippines.

Upon receiving the first of the installments, Aguinaldo and 25 of his closest associates left their headquarters at Biak-na-Bato and made their way to Hong Kong, according to the terms of the agreement. Before his departure, Aguinaldo denounced the Philippine Revolution, exhorted Filipino rebel combatants to disarm and declared those who continued hostilities and waging war to be bandits. Despite Aguinaldo’s denunciation, some of the rebels continued their armed revolt against the Spanish colonial government. According to Aguinaldo, the Spanish never paid the second and third installments of the agreed upon sum.

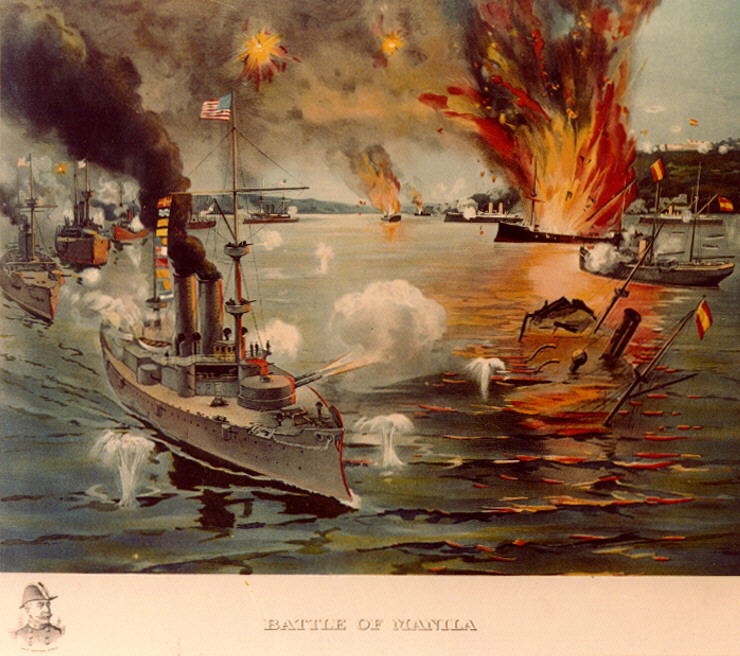

After only four months in exile, Aguinaldo decided to resume his role in the Philippine Revolution. He departed from Singapore aboard the steamship Malacca on April 27, 1898. He arrived in Hong Kong on May 1,which was the day that Commodore Dewey’s naval forces destroyed Rear-Admiral Patricio Montojo‘s Spanish Pacific Squadron at the Battle of Manila Bay. Aguinaldo then departed Hong Kong aboard the USRC McCulloch on May 17, arriving in Cavite on May 19.

Less than three months after Aguinaldo’s return, the Philippine Revolutionary Army had conquered nearly all of the Philippines. With the exception of Manila, which was surrounded by revolutionary forces some 12,000 strong, the Filipinos rebels controlled the Philippines. Aguinaldo turned over 15,000 Spanish prisoners to the Americans, offering them valuable intelligence. Aguinaldo declared Philippine independence at his house in Cavite El Viejo on June 12, 1898.

The Philippine Declaration of Independence was not recognized by either the United States or Spain on the grounds that it did not give power to the people and only left an elite few in charge. The Spanish government ceded the Philippines to the United States in the 1898 Treaty of Paris, which was signed on December 10, 1898, in consideration for an indemnity for Spanish expenses and assets lost.

On January 1, 1899, Aguinaldo declared himself President of the Philippines—the only president of what would be later called the First Philippine Republic. He later organized a Congress at Malolos in Bulacan to draft a constitution.

The Relationship Sours

- What was Aguinaldo’s understanding his relationship with the Americans? What were the Americans’ understanding? Whose version do you believe and why?

- Would things be different if Filipino troops had captured Manila, raising their flag over Fort Santiago?

- How did the Filipino relationship with the Americans change once the Spanish were defeated?

On April 22, 1898, while in exile, Aguinaldo had a private meeting in Singapore with United States Consul E. Spencer Pratt, after which he decided to again take up the mantle of leadership in the Philippine Revolution. According to Aguinaldo, Pratt had communicated with Commodore George Dewey (commander of the Asiatic Squadron of the United States Navy) by telegram, and passed assurances from Dewey to Aguinaldo that the United States would recognize the independence of the Philippines under the protection of the United States Navy. Pratt reportedly stated that there was no necessity for entering into a formal written agreement because the word of the Admiral and of the United States Consul were equivalent to the official word of the United States government. With these assurances, Aguinaldo agreed to return to the Philippines.

Pratt later contested Aguinaldo’s account of these events, and denied any “dealings of a political character” with Aguinaldo. Admiral Dewey also refuted Aguinaldo’s account, stating that he had promised nothing regarding the future:

“From my observation of Aguinaldo and his advisers I decided that it would be unwise to co-operate with him or his adherents in an official manner. … In short, my policy was to avoid any entangling alliance with the insurgents, while I appreciated that, pending the arrival of our troops, they might be of service.”

Filipino historian Teodoro Agoncillo writes of “American apostasy,” saying that it was the Americans who first approached Aguinaldo in Hong Kong and Singapore to persuade him to cooperate with Dewey in wresting power from the Spanish. Conceding that Dewey may not have promised Aguinaldo American recognition and Philippine independence (Dewey had no authority to make such promises), he writes that Dewey and Aguinaldo had an informal alliance to fight a common enemy, that Dewey breached that alliance by making secret arrangements for a Spanish surrender to American forces, and that he treated Aguinaldo badly after the surrender was secured. Agoncillo concludes that the American attitude towards Aguinaldo “…showed that they came to the Philippines not as a friend, but as an enemy masking as a friend.”

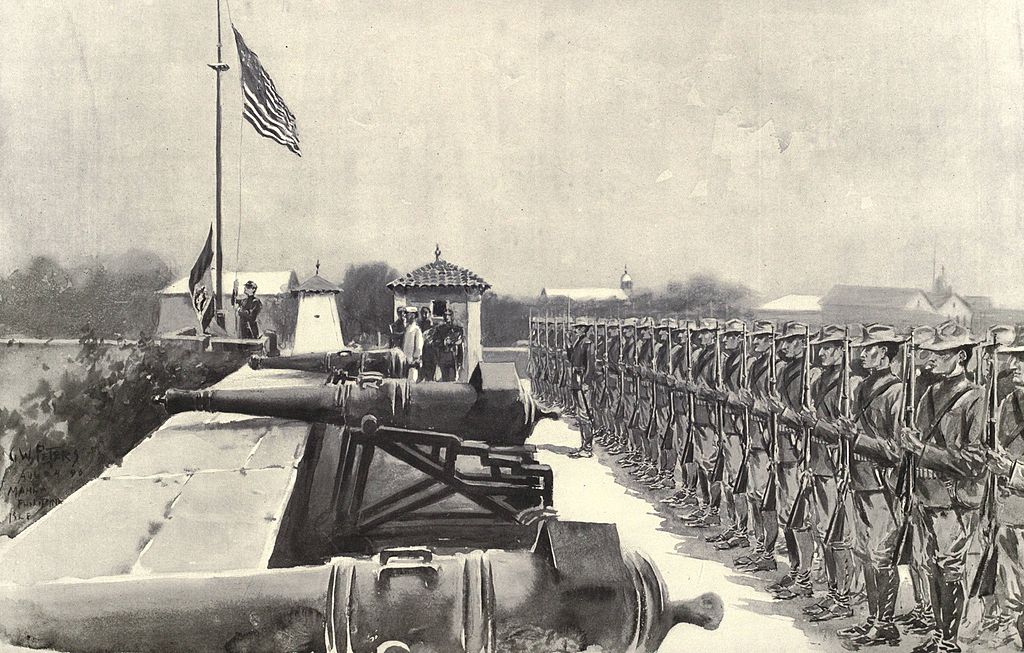

The first contingent of American troops arrived in Cavite on June 30, the second under General Francis V. Greene on 17 July, and the third under General Arthur MacArthur on 30 July. By this time, some 12,000 U.S. troops had landed in the Philippines.

Aguinaldo had presented surrender terms to Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines Basilio Augustín, who refused them. Augustín had thought that if he really needed to surrender the city, he would do so to the Americans. On 16 June, warships departed Spain to lift the siege, but they altered course for Cuba where a Spanish fleet was imperiled by the U.S. Navy. Life in Intramuros (the walled center of Manila), where the normal population of about ten thousand had swelled to about seventy thousand, had become unbearable. Realizing that it was only a matter of time before the city fell, and fearing vengeance and looting if the city fell to Filipino revolutionaries, Governor Augustín suggested to Dewey that the city be surrendered to the Americans after a short, “mock” battle. Dewey had initially rejected the suggestion because he lacked the troops to block Filipino revolutionary forces, but when Merritt’s troops became available he sent a message to Fermin Jáudenes, Augustín’s replacement, agreeing to the mock battle. Spain had learned of Augustín’s intentions to surrender Manila to the Americans, which had been the reason he had been replaced by Jaudenes.

Merritt was eager to seize the city, but Dewey stalled while trying to work out a bloodless solution with Jaudenes. On 4 August, Dewey and Merritt gave Jaudenes 48 hours to surrender; later extending the deadline by five days when it expired. Covert negotiations continued, with the details of the mock battle being arranged on 10 August. The plan agreed to was that Dewey would begin a bombardment at 09:00 on 13 August, shelling only Fort San Antonio Abad, a decrepit structure on the southern outskirts of Manila, and the impregnable walls of Intramuros. Simultaneously, Spanish forces would withdraw, Filipino revolutionaries would be checked, and U.S. forces would advance. Once a sufficient show of battle had been made, Dewey would hoist the signal “D.W.H.B.” (meaning “Do you surrender?), whereupon the Spanish would hoist a white flag and Manila would formally surrender to U.S. forces. This engagement went mostly according to plan and is known as the Mock Battle of Manila.

The Filipinos would not be allowed to enter the city. On the eve of the battle, Brigadier General Thomas M. Anderson telegraphed Aguinaldo, “Do not let your troops enter Manila without the permission of the American commander. On this side of the Pasig River you will be under fire.” On August 13, American forces captured the city of Manila from the Spanish.

Before the attack on Manila, American and Filipino forces had been allies against Spain in all but name. After the capture of Manila, Spanish and Americans were in a partnership that excluded the Filipino insurgents. Fighting between American and Filipino troops had almost broken out as the former moved in to dislodge the latter from strategic positions around Manila on the eve of the attack. Aguinaldo had been told bluntly by the Americans that his army could not participate and would be fired upon if it crossed into the city. The insurgents were infuriated at being denied triumphant entry into their own capital, but Aguinaldo bided his time. Relations continued to deteriorate, however, as it became clear to Filipinos that the Americans were in the islands to stay.

On December 21, 1898, President William McKinley issued a Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation, which read in part, “…the earnest wish and paramount aim of the military administration to win the confidence, respect, and affection of the inhabitants of the Philippines by assuring them in every possible way that full measure of individual rights and liberties which is the heritage of free peoples, and by proving to them that the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule.”

Major General Elwell Stephen Otis—who was Military Governor of the Philippines at that time—delayed its publication. On January 4, 1899, General Otis published an amended version edited so as not to convey the meanings of the terms “sovereignty,” “protection,” and “right of cessation,” which were present in the original version. However, Brigadier General Marcus Miller—then in Iloilo City and unaware that the altered version had been published by Otis—passed a copy of the original proclamation to a Filipino official there.

The original proclamation then found its way to Aguinaldo who, on January 5, issued a counter-proclamation: “My government cannot remain indifferent in view of such a violent and aggressive seizure of a portion of its territory by a nation which arrogated to itself the title of champion of oppressed nations. Thus it is that my government is disposed to open hostilities if the American troops attempt to take forcible possession of the Visayan islands. I denounce these acts before the world, in order that the conscience of mankind may pronounce its infallible verdict as to who are true oppressors of nations and the tormentors of mankind. In a revised proclamation issued the same day, Aguinaldo protested “most solemnly against this intrusion of the United States Government on the sovereignty of these islands.”

Otis regarded Aguinaldo’s proclamations as tantamount to war, alerting his troops and strengthening observation posts. On the other hand, Aguinaldo’s proclamations energized the masses with a vigorous determination to fight against what was perceived as an ally turned enemy.

Outbreak

- Why did Aguinaldo initially offer a cease fire? Why do you think the Americans refused a cease fire when Aguinaldo offered one?

On the evening of February 4, Private William W. Grayson—a sentry of the 1st Nebraska Volunteer Infantry Regiment, under orders to turn away insurgents from their encampment, fired upon an encroaching group of four Filipinos—fired the first shots of the war at the corner of Sociego and Silencio Streets, in Santa Mesa. According to Grayson’s account, he called “Halt!” and, when the four men responded by cocking their rifles, he fired at them. Upon opening fire, Grayson claims to have killed two Filipino soldiers; Filipino historians maintain that the slain soldiers were unarmed.

The following day, Filipino General Isidoro Torres came through the lines under a flag of truce to deliver a message from Aguinaldo to General Otis that the fighting had begun accidentally, saying “the firing on our side the night before had been against my order,” and that Aguinaldo wished for the hostilities to cease immediately and for the establishment of a neutral zone between the two opposing forces. Otis dismissed these overtures, and replied that the “fighting, having begun, must go on to the grim end.” On February 5, General Arthur MacArthur ordered his troops to advance against Filipino troops, beginning a full-scale armed clash between 19,000 American soldiers and 15,000 Filipino armed militiamen.

Aguinaldo then reassured his followers with a pledge to fight if forced by the Americans, whom he had come to see as new oppressors, picking up where the Spanish had left off:

“It is my duty to maintain the integrity of our national honor, and that of the army so unjustly attacked by those, who posing as our friends, attempt to dominate us in place of the Spaniards.

“Therefore, for the defense of the nation entrusted to me, I hereby order and command: Peace and friendly relations between the Philippine Republic and the American army of occupation are broken—and the latter will be treated as enemies with the limits prescribed by the laws of War.”

In this Battle of Manila, American casualties totaled 238, of whom 44 were killed in action or died from wounds. The U.S. Army’s official report listed Filipino casualties as 4,000, of whom 700 were killed, but this is guesswork, and it is only the unfortunate opening battle of a much larger war that would drag on in one form or another for more than a decade.

That story is told in The Brutality of the Philippine-American War.

Activities

- There is a long tradition of resistance to colonial rule in the Philippines.

Juan Sumuory is celebrated in the Gallery of Heroes. (Manila, Philippines, 2018.) Couple of this with the country’s strong Catholicism – with its tradition of sainthood and martyrdom – and you have nation that is very aware of those who have sacrificed to advance the cause of the Filipino. Manila’s Rizal Park features the Gallery of Heroes, a row of bust sculpture monuments of historical Philippine heroes. These include: Andres Bonifacio, Juan Sumuroy, Aman Dangat, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, Gregorio Aglipay, Sultan Kudarat, Juan Luna, Melchora Aquino, Rajah Sulayman, and Gabriela Silang. Choose one of these personalities to commemorate in your own classroom. Write a brief description of their accomplishments to accompany a piece of artwork that celebrates their life for those who aren’t aware.

- Jose Rizal never specifically advocated violence or even open revolt against

Jose Rizal famously declined the Spanish offer of a carriage ride to his execution site. Instead, he walked, and today, bronze footprints mark his path from Fort Santiago to today’s Rizal Park, a memorial that literally allows one to walk in the footsteps of a national hero. the Spanish, pushing instead for political reforms within the colonial structure. He wrote with such clarity and passion, however, that he become a symbol to revolutionaries – and this is why the colonial authorities decided he needed to die, in a plan that ultimately backfired, transforming him into a martyr. Debate with your class – “Does a national hero need to be a warrior – a violent figure? If not, why are so many warriors celebrated the world over as national heroes?”

- Rudyard Kipling wrote a famous poem about the U.S. and its conquest of the Philippines. It is called “The White Man’s Burden.” The poem became so famous that it became the subject of parody as well. Read both the poem and one of its parodies and discuss it with your classmates using the included questions to help guide you.

- Stereoscopic Visions of War and Empire – This exhibit juxtaposes the visual message presented by the stereoscopic images with excerpts from the letters written by U.S. soldiers that were first published in local newspapers and later collected in the Anti-Imperialist League’s pamphlet, allowing us to get a glimpse of the Philippine-American War as it was presented to Americans at home, reading the news or entertaining friends in their parlors.

- In The Trenches: Harper’s Weekly Covers the Philippine-American War – How did the American media cover the war in the Philippines? An excerpt from “In The Trenches” by John F. Bass, originally published in Harper’s Weekly.

Read more on this subject -> The Origins of the Philippine-American War ◦ The Brutality of the Philippine-American War ◦ The Philippines in the American Empire ◦ “The White Man’s Burden”: Kipling’s Hymn to U.S. Imperialism ◦ Stereoscopic Visions of War and Empire ◦ In The Trenches: Harper’s Weekly Covers the Philippine-American War ◦ Ninoy and Marcos – “A Pact with the Devil is No Pact at All.”

FURTHER READING

History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos by Luis Francia.

THIS LESSON WAS INDEPENDENTLY FINANCED BY OPENENDEDSOCIALSTUDIES.ORG.

If you value the free resources we offer, please consider making a modest contribution to keep this site going and growing.

It is one of the best and detailed article I ever read about the origins of america-Philippines war. Thank you for mentioning and throwing lights on several associated stories.

LikeLike