The Economic Impact of the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution

Thirty-three years have already passed since the Filipino people gathered together for the monumental overthrowing of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

As we celebrate the anniversary of the restoration of the country’s civil liberties and democracy, here’s a look at how the popular uprising put a stop to the government’s greedy fiscal management and helped stabilize the economy.

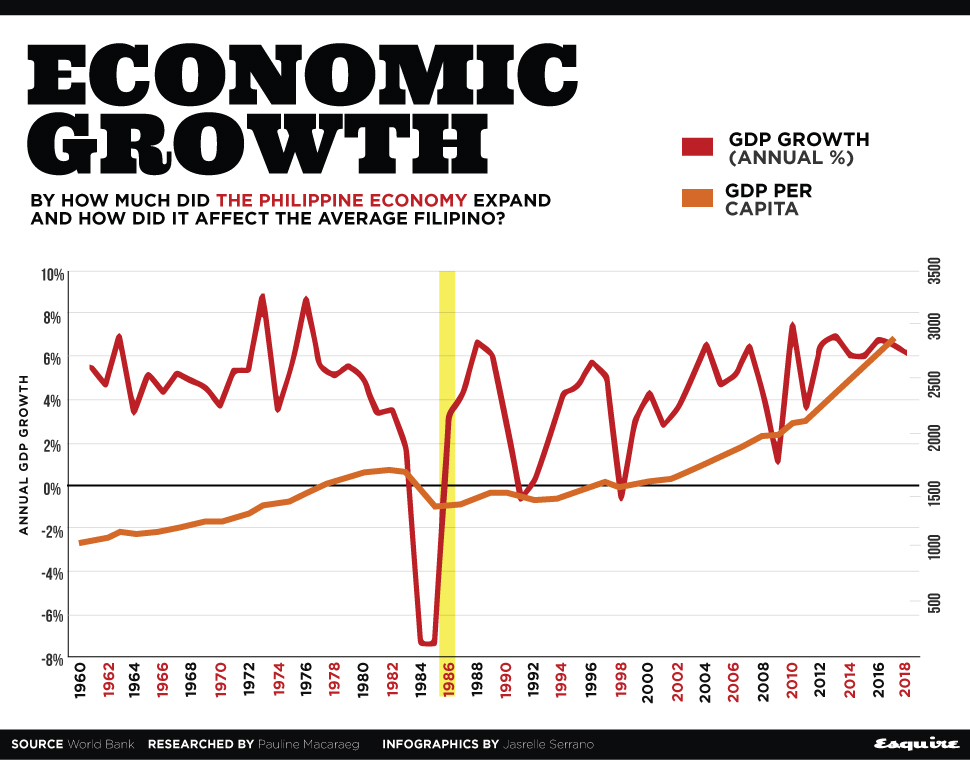

What probably best describes the Philippine economy during martial law were the erratic booms and busts experienced from 1972 to 1986.

Government records show the economic output of the country as measured by the gross domestic product (GDP) reached historic highs during martial law—climbing to

But the same dataset also shows how these “achievements” were short-lived. Only eight years later, the economy also plunged to record lows of -7.3 percent toward the end of the Marcos regime in 1984 and 1985.

Economic growth noticeably started rising again after the EDSA People Power in 1986. To be sure, it did fall a couple of times since then due to other financial crises that transpired but the busts that happened after the revolution never exceeded the figures recorded during martial law.

The average Filipino’s standard of living was way better pre-martial law, too, as measured by the country’s GDP per capita or the country’s economic output per person.

In fact, compared to its neighboring countries, the Philippine economy was one of the best performers.

By late 1960s the country’s GDP was above all the other four founding members of the Association of Southeast Nations (ASEAN), namely Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore. It was also the third best in terms of GDP per capita

However, the country’s GDP per capita also took a plunge in 1983—or when former Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., the prominent opposition leader back then, was assassinated. (Academics from the University of the Philippines believe that while the economy was already falling before 1983, it was Aquino’s assassination triggered the full-blown economic crisis.)

The Philippines’ GDP per capita started to increase again after the EDSA revolution. But the crisis that transpired had already caused long-term consequences to the economy, essentially making the country lose two decades of economic growth already.

When the country’s GDP per capita started to recover only in the early 2000s, the Philippines had already been left behind by its neighbors in Southeast Asia.

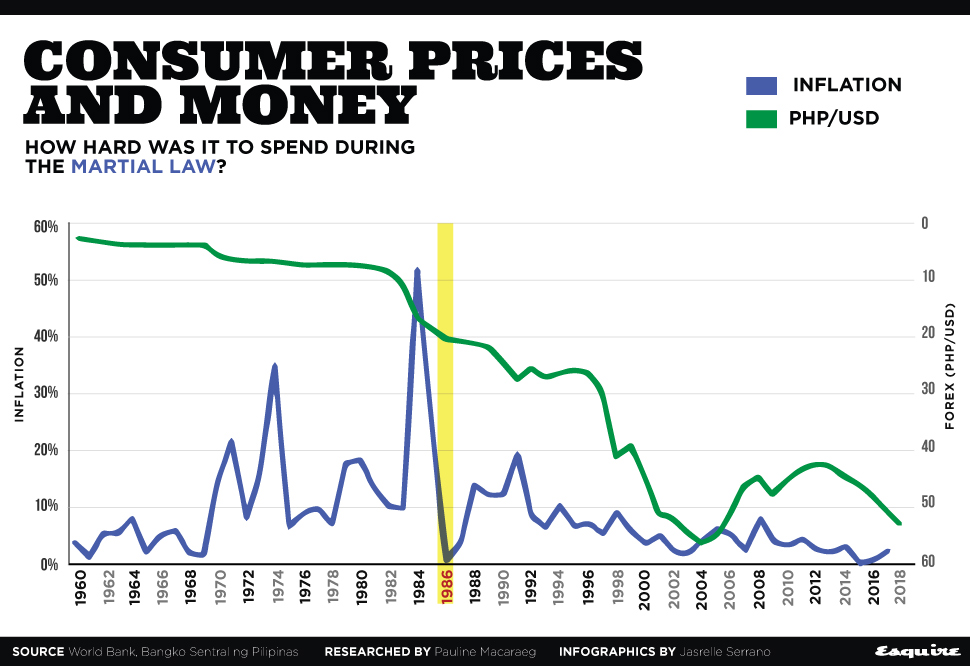

It was not only economic growth that was unstable before the revolution

This is contrary to many Marcos supporters' declarations that prices of food, rice, and other essential goods were more affordable when martial law was in place. Inflation rates recorded from 1972 to 1985 were remarkably higher compared to the years before and after that period, indicating a faster increase in prices.

In 1986 this fell to just 1.15 percent. Since then, narrower swings in consumer price increases were also observed.

Meanwhile, the Philippine currency was already slowly depreciating in the years prior to martial law, but the steep fall started in 1983. It depreciated against the dollar by 30 percent from just P8.54/$1 to P11.11/$1. The next year it further went down by 50 percent to P16.7/$1.

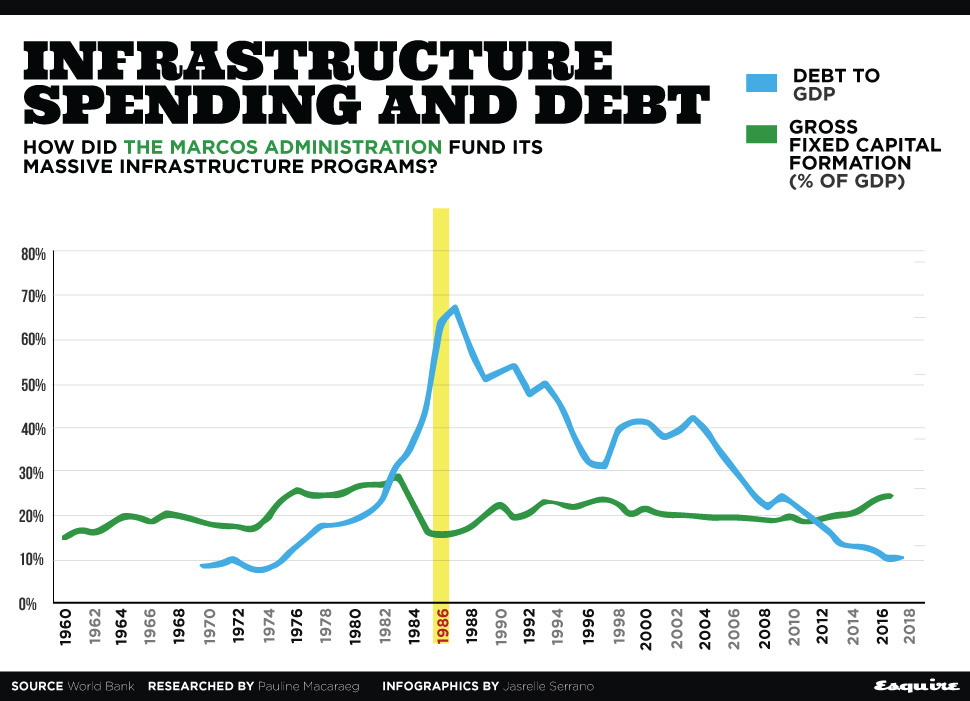

Another favorite argument by Marcos supporters is the supposedly “golden age of Philippine infrastructure” during the martial law.

It is true that many bridges, roads, buildings, and many other infrastructure projects were developed during this period. The country’s gross fixed capital formation confirms that, as it indeed rose by 69 percent from 1972 to 1983. This indicates a high increase in the physical assets in both the public and private sectors, including investments and construction. However, these developments come at a high cost.

Foreign debt also rose during this time, significantly at a higher and steeper slope. This indicates that while the government was big in infrastructure spending, the amount that it was borrowing from foreign banks was way bigger than needed.

In 1984 the gross fixed capital formation started falling, but foreign debt continued to rise. This indicates that the Marcos regime was still incurring debts in the following years but is not really putting the funds to infrastructure spending

By 1983, the government could no longer pay its loans and declared a debt moratorium, resulting in the plunge in infrastructure construction.

After the revolution, the country’s debts started to decrease again but the amount of debt incurred by the Marcos administration was already so big that the country had been struggling to pay for it for years.

Moreover, since portions of the loans went to either unproductive spending or were outrightly stolen instead of infrastructure spending, the country’s gross fixed capital formation stayed relatively steady after the EDSA revolution.